Scratchpads and why you and I and language models need them.

Yapping

Till about a month and a half ago, I was looking at papers on LLM reasoning, especially where they bypass using thinking tokens and perform latent reasoning. In hindsight, that was a time to which I raise my glass and toast it to “Science”. It started off with a project on DeepFake detection, where I had an idea to rephrase the problem of DeepFake detection into a reasoning task from a classification task. I’m pretty sure I got into that line of thought because of multiple factors like a lack of high quality annotated data and compute power. Well the idea did not work out the way I had imagined it would, but I think I understand thinking tokens better now.

What is Reasoning?

It is important that we first define what reasoning is. The end goal of reasoning is that we have the correct answer to our task AND that we arrive to this conclusion through sound logic. Our process looks something like

\[\text{task} \rightarrow \text{thinking} \rightarrow \text{answer}\]This is how humans reason about things. We take available information, think and have an answer. But what exactly happens during tinking? I mean, we distill information, track how the state of this information changes and arrive to a conclusion from the final state. Based on the task, we may ponder for a while or arrive at a conclusion quickly, or we may need a “memory” to store and track information, in the form of a “rough work” area.

LLMS & Reasoning

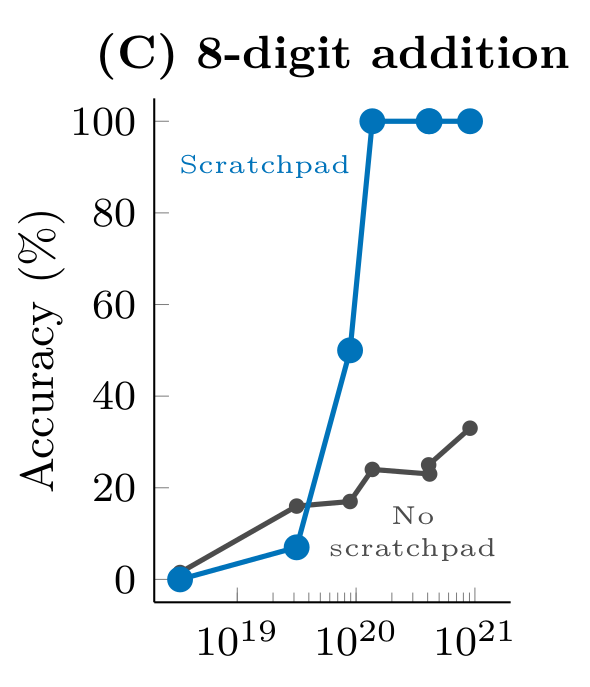

On first thought, one may think language models should be capable of reasoning. They are trained with a language modelling objective, processing information token by token so that line of thought is not entirely wrong. The thing is, the model has full context of the task only at the last token- it has only one forward pass to come up with an answer. This is kinda insufficient compute time for the model to do reasoning and find an answer. This is somewhat seen in GPT-3’s performance on Arithmetic tasks (Brown et al., 2020), where next token prediction only sometimes works because there is no implicit or explicit state tracking going on (as a matter of fact, next token prediction does not even teach arithmetic rules).

A simple way to improve the reasoning performance is to provide the model with a ‘scratchpad’ to track information and fine-tune it by providing step-by-step ‘reasoning’, also called Chain of Thought. To do this, we’d need a dataset $\mathcal{D}$ comprising of tasks $x$, rationales $r$ and answers $y$. During test time, the model is provided the task and it has to generate the correct reasoning following with the solution. The rationales usually go between the <scratch>...</scratch> tokens. This scratchpad is a simple yet clever adaptation to the model to provide it with a way to track state of information, but more importantly, adapt compute time to the problem. We can see the performance improvement that a model sees on arithmetic in (Wei et al., 2022) and (Wei et al., 2022).

What purpose does the scratchpad really serve?

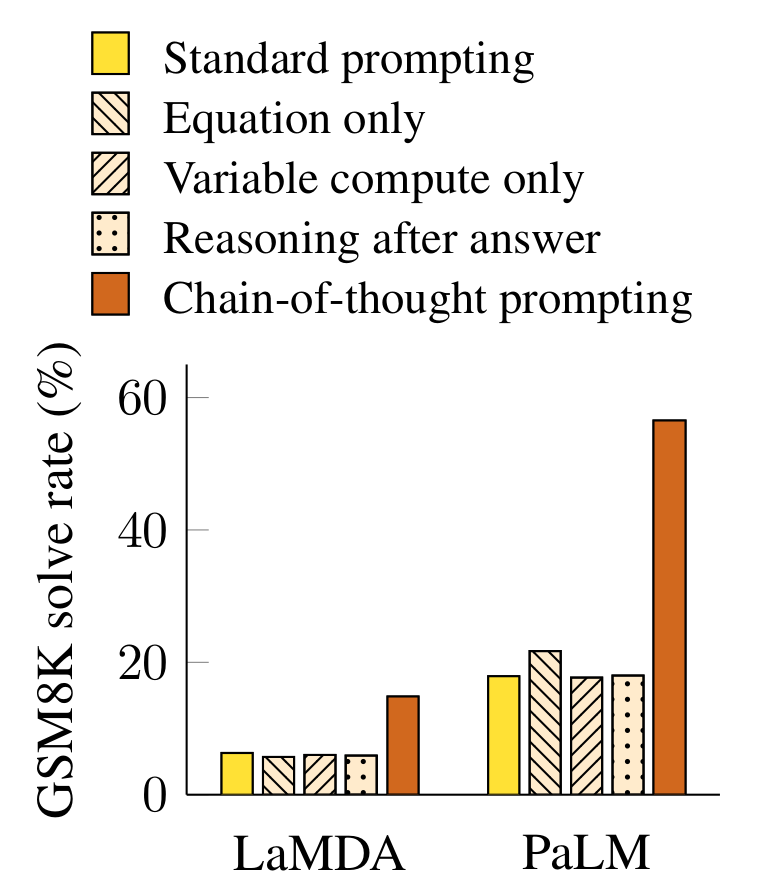

Contrary to what one may assume, the scratchpad has two purposes- information state tracking and adapting compute time. (Wei et al., 2022) tests the PaLM-540B and LaMDA in 5 scenarios: standard prompting, prompts with only equations, with a scratchpad with $[\ldots]$ instead of CoT steps, with CoT reasoning after answer and finally with scratchpad and CoT reasoning steps. The results showed that the scenario 1, 2, 3 and 4 have similar performance, meaning that adapting compute meaninglessly has no impact on the reasoning performance. Scenario 4 assess if the model uses the content of the scratchpad for reasoning. I have little knowledge as to why LaMDA performs so bad.

Can we elicit reasoning without rationales?

I think trying to elicit reasoning without rationales is very difficult. Training on just ${(x,y)}$ not only fails to provide a strong learning signal, it also gives the model no mechanism to adapt its compute time to the problem. With no explicit relationship between the task and the solution path, the model is incentivized to shortcut—and often falls back to hallucinating plausible answers instead of reasoning.

There is active research into models that can adapt their compute dynamically, such as S1 (Muennighoff et al., 2025), Hierarchical Reasoning Model (Wang et al., 2025), and more recently TRMs (Jolicoeur-Martineau, 2025), but this remains an open problem. A common thread among this area of research is to make the model generate a latent form of reasoning for the task and to modify the architecture to be recursive, allowing the model to decide how much computation a problem requires.

Conclusion

In hindsight, using scratchpads to elicit reasoning from LLMs is a simple but cool trick to use the language modelling capability of the LLM not just for adapting compute time but also providing a sort of information state tracking.

2025

- s1: Simple test-time scaling2025

- Hierarchical Reasoning Model2025

- Less is More: Recursive Reasoning with Tiny Networks2025

2022

- Chain-of-thought prompting elicits reasoning in large language modelsIn Proceedings of the 36th International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, New Orleans, LA, USA, 2022

- Emergent Abilities of Large Language ModelsTransactions on Machine Learning Research, 2022Survey Certification

2020

- Language Models are Few-Shot LearnersIn Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 2020